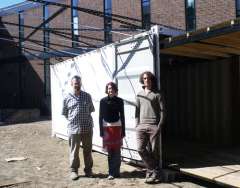

Don’t look like much but it works

A student architecture project has produced a new off-grid hub for disaster relief. Students at the Minnesota U plan to send the hub to New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward. The cheap, practical off-grid pod can provide water and power wherever it is parachuted in. Much of the Lower Ninth district remains behind in reconstruction efforts, lacking electricity or running water, and the portable sanitation center will certainly be a boon to the area, said Greta Gladney of the Renaissance Project, a nonprofit organization in the Lower Ninth.

Are You Ready? An In-depth Guide to Citizen Preparedness (US Dept. of Homeland Security, FEMA, Citizen Corps Uniting Communities Preparing the Nation)

For the past few months, 16 architecture seniors and adjunct professors John Dwyer and Tom Westbrook have been designing and building a one-of-a-kind, portable, self-contained water and sanitation center. Send us a photo guys, if you read this.

The prototype is called a “clean hub”, made from an old, 20-foot-long storage container. It houses a bathroom complete with a composting toilet and a solar shower, a 4,400-gallon water tank, a foot pump-powered sink, and water collection and filtration systems.

Running on two solar panels and a 1500-watt battery, the hub also provides sufficient electricity to power itself, with enough left over to run a small appliance, such as a laptop.

“It’s completely off-grid,” Westbrook said. “We wanted to have this thing not leave a big footprint on the earth, in fact quite the opposite.”

The hub is also fairly economic. With most of the parts either donated or recycled, it’s estimated the total cost is less than $5,000 (not accounting for hours of class time spent designing and laboring).

The low cost has also caught the attention of officials at both the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the World Bank, who are interested in the aid a hub could provide people caught in a natural disaster or living in a refugee camp.

“We wanted to develop something that was very low cost. If you look at the cost of a FEMA trailer, it’s ridiculously expensive and has a very short lifetime,” Westbrook said. “This is something that can provide a lot of the things a FEMA trailer doesn’t, like power and self-contained sanitation, and be substantially cheaper.”

FEMA trailer controversy

Last summer, the safety of living in FEMA trailers was questioned when reports indicated they were exposing inhabitants to a toxic gas that could pose both immediate and long-term health risks.

Air quality tests of 44 FEMA trailers conducted by the Sierra Club in April 2006 found concentrations of the gas described as “elevated”, a level nearly equal to what a professional embalmer would be exposed to on the job. This concentration level is capable of causing watery eyes, burning in the eyes and throat, nausea, and respiratory distress in some people.

FEMA defended the trailers, though acknowledged that the high heat and humidity in the Gulf Coast could increase the rate of the gas, formaldehyde, “outgassing” from wood products trailers, but added that ventilation should quickly take care of any problem.

Mary DeVany, an industrial hygienist from Vancouver, who has studied the formaldehyde issue, agrees that the high heat and humidity in the hurricane-ravaged zone exacerbate the problem. But she believes that the higher-than-usual readings in the FEMA trailers could be the result of the rush to manufacture the trailers in the wake of Katrina.

The team doesn’t plan to wait around for the federal government, however. The hub will shortly be on its way to New Orleans. Architecture senior Sandra Wahba said she hopes to accompany the hub.

“I feel so attached to this that it’s like my job to go see this perform for us,” she said.

Students’ work

Though the project guidelines were first conceived by the instructors, from then on the students took over.

“We felt strongly it had to be their project. So instead of them providing labor for our designs, it was the other way around,” says Westbrook. “I’ve made probably about a million runs to Home Depot.”

He and Dwyer have been there to provide guidance and instructions, letting the seniors decide the scope of the project.

“We told them early on, at the beginning of the semester that they were digging their own graves and deciding how deep to dig,” he said.

As is often the case with construction, the students had to contend with the weather.

“It rained for the first month we worked on it, which probably affected the roof team the most,” Christensen said.

Senior Kyle Erickson said other challenges the students had to navigate their way through included mapping out the hub’s plumbing and electrical fixtures – things they didn’t know much about but had to learn as they went.

It seems he was pleased with the final result though:

“Having something you’ve actually built going somewhere for a good cause is really rewarding.”