From 2010 onwards, off-grid.net ran stories about smart meters – like this one – predicting that the meters would be an expensive failure. Finally the world is coming around to our way of thinking.

The introduction of smart meters was bungled pretty well everywhere – but especially in the UK and Australia – where weak and incompetent regulators were at the mercy of lobbyists, and any talented opposition was quickly hired by the Utility companies.

Even the Financial Times now agrees that the UK “has made dumb mess of (the) £13.5bn smart meter scheme.” Calling it a “vital project for future of energy,” the FT says it isone of the UK’s most expensive infrastructure projects, is four years behind schedule and is expected to exceed its initial budget.

The UK government announced in 2008 that energy suppliers would be responsible for fitting smart meters. Fifteen years later, 32mn of 57mn meters in UK homes and small businesses are smart devices. The government initially estimated it would cost £13.5bn for energy suppliers. Companies would recover their costs via customer energy bills and deliver £19.5bn in benefits. Those estimates were in 2011 money and do not account for recent high inflation.

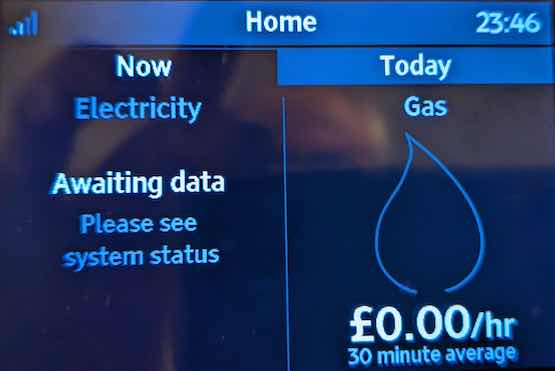

The problems with the smart meter rollout have been many and varied. Some early models stopped working. Others displayed false and very high readings. They are not suitable for certain areas and buildings where there is poor mobile coverage. The list goes on. Ministers wanted the programme to complete in 2019. Even before the pandemic, the government admitted the finish date could be as late as 2024. Earlier this year, ministers consulted on revised targets for suppliers to install meters in at least 80 per cent of homes, and 73 per cent of small businesses, by the end of 2025.

Those in charge of smart meter programmes at energy suppliers think even the revised targets are unrealistic. Households that are inclined to make the switch have mostly already done so, they say. They are now faced with trying to persuade sceptical households or those that have yet to even engage with their inquiries. Adding to these difficulties, some smart meters will need to be updated when 2G and 3G networks are phased out in the early part of next decade.

Energy companies will increasingly be able to offer households with smart meters tariffs that are cheaper if energy is used off-peak. Smart meters could be made a requirement for all new homes. Remarkably that is not the case. They could also change the rating system for energy performance certificates to include smart meters, which could tempt homeowners seeking to sell their property.

Smart meters have become emblematic of the incompetence and inefficiency of the electricity industry both in the UK and worldwide.

But there is one further criticism that we did not think of in 2009, and in fact only occurred to us recently. Smart meter could have been designed to facilitate direct sales between consumers – peer-to-peer trading in home-generated electricity – instead of selling it back to the grid at a rip-off low tariff, householders could sell to the neighbours for slightly less than their utility company would pay.

Smart meters could still enable householders to take back control of their own power, but that would require a huge leap of imagination from regulators and governments.