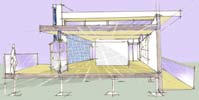

Early sketch of MIT’s Solar 7

Members of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Solar Decathlon team head out for Washington, D.C. next week taking with them a house they designed and built from scratch. Dubbed “Solar 7,” it’s a home of the future: self-sufficient, powered purely by the sun, and MIT’s entry in an international competition for the most efficient – and livable – solar house.

The team hits the road Oct. 1, heading to the National Mall for the solar decathlon. There, in the shadow of the Capitol Building, Solar 7 will be judged against 19 other solar homes not only for architectural and engineering excellence, but also comfort, marketability, and energy efficiency.

But before it gets to compete, the team must finish building the house.

As it stands, with a little more than a week to go, Solar 7 is not quite finished. The bathroom needs fixtures, not to mention a toilet and a tub. Walls stand unfinished, doorways are missing doors, and there’s no plumbing. At the site, volunteers paint and screw in panels while a team checks the wiring, stepping nimbly over stray tools strewn across the house’s half-finished floor.

“I’m stressed about everything,” lead builder Tom Pittsley said. “We’ve got … days to build a house and tear it apart.”

“Take a deep breath before the storm,” Corey P. Fucetola G, the project manager, said.

Pittsley laughed. “This is the storm,” he said.

Solar powered

The challenge of the Solar Decathlon, a contest that occurs every two years and is sponsored by the Department of Energy, is not just to build an energy efficient house. It’s to build an energy positive one: a house that can provide its own heating and cooling and electricity, year-round, from the power of the sun.

So it’s no surprise that Solar 7 sports a hefty array of 42 solar panels on its roof, providing a total of over 9,000 watts to 800 square feet of living space. “It’s way more than a house this size needs,” the team’s technology adviser Jim Dunn said. “We over-designed it to have plenty of power for the competition.”

Solar 7’s panels gather so much electricity that, in fact, two had to be taken offline, or the combined output would have blown the inverters which route the electricity to appliances in the home, Fucetola said.

Last Friday, the house switched over to running completely on solar energy, making it the first officially off-the-grid building in Cambridge. The reality of this milestone has not yet set in for all of the team. “Hey, that’s a live panel there!” Dunn said to a volunteer near an exposed knot of wiring in the wall. “It’s running 230 volts.”

At the competition, the electricity will power appliances and charge an electric car. To demonstrate that Solar 7 is livable, team members will cook meals in the house for four days, using stoves running off solar energy. They will wash and dry laundry, do the dishes, watch TV and run a computer – all typical household tasks, performed in a house that is anything but.

Aside from solar panels, Solar 7 takes advantage of the sun’s power in other ways. On the south-facing wall, rows of black pipes use the sun to heat up water that will run through small tubes under the floorboards. Not only does this technique save heating costs, it also heats the house more comfortably, Fucetola said.

On the same south-facing side, a large, milky white panel heats up during the day and radiates warmth at night – a traditional green building feature called a “tromme wall.” But Solar 7’s wall is comprised of a layer of water sandwiched between white strips of an advanced aerogel that insulates while letting light through.

The aerogel wall is not the only technological flourish in Solar 7. Although competition rules limit teams to commercially available materials, Fucetola said the MIT team enjoyed the support of industry leaders eager to work with the Institute. Several components of the house, including the power inverters and the warm wall, were obtained before they were commercially available. Others, like the washing machine and kitchen appliances, were donated outright.

“[Companies] want to work with MIT students, that’s what we have to sell,” Fucetola said.

Building a house of the future

To call Solar 7 a purely MIT effort, however, would be ignoring the wide community support the project has garnered and grown to depend on.

Although the project began under the auspices of the MIT Department of Architecture and Planning in 2005, it was dropped by June 2006 over concerns on Institute funding, Fucetola said. Eight months into the project, no funds had been raised outside of what MIT could provide, so the department decided to call everything off, Fucetola said. Though the Department of Energy gives $100,000 to every team that is selected to compete, the sum is only a fraction of what a competitive team needs to build a house.

“[The architecture department] thought if we were going to fail, we should choose to fail fast and early,” Fucetola said. “We said, ‘We’re not going to fail.'”

That June, Fucetola turned to Kurt L. Keville ’90, originally one of the team’s faculty advisers, to assume the role of principal investigator. For the next six months, under Fucetola’s lead, the team worked to raise money and their profile. “We did as much outreach as possible,” Fucetola said. “We had poster sessions. We went to community events and tried to get people involved.”

Soon, the team had drawn out people from all parts of the Cambridge community: students and faculty not just from MIT but volunteers from Harvard University, Boston University, and Boston Architectural College; students from local high schools; and electricians, plumbers, master builders, and carpenters who donated their time.

Kevin Horne, one of the architects for the project, calls the team “the motliest of motley crews.” Horne, who is himself a student at the Boston Architectural College, joined the team in January looking for experience with green building. “People come for all kinds of reasons,” Horne said, “but we’re all interested in sustainable architecture. [Solar Decathlon] gives us the chance to experiment, to play, to share ideas.”

Plans for Solar 7 were finalized early this year through a series of difficult design negotiations. “The house probably went though 50 major redesigns,” Fucetola said.

Despite conflict over the details, Fucetola said that the team agreed early on to make good use of natural light, a commitment that led to the numerous skylights tucked between Solar 7’s swooping roof, as well as the translucent, aerogel-lined warm wall. The team also strives to use only environmentally friendly methods and materials. Instead of virgin lumber, they used particleboard, which is made from wood scraps and sawdust. The floor and ceiling are bamboo; the wall panels are made from recycled wheat. The roof is covered in tiles made from recycled tires.

As the competition day nears, Fucetola said he is not as concerned about how well Solar 7 will do. He said he only hopes that the house will help persuade politicians and the public the viability of sustainable architecture using renewable energy. “Solar 7 will go in front of people who decide policy,” he said. “If we can make it work, then they can make appropriate decisions about the environment.”

See https://web.mit.edu/ solardecathlon/ for more information.