I ran across a book and an article all about making your own root cellar, this being the end of the summer, beginning of fall, having a cheap and easy to put together root cellar is the thing to have, both for budding homesteaders to seasoned off-gridders.

I find that when “something” keeps popping up in front of me, there is a reason and I pay attention, so here it is enjoy! You can see a link to the root cellar book at the end.

In our agrarian past, we didn’t have a grocery store in every town receiving shipments of fresh fruits and vegetables from all corners of the world on a daily basis. Food preservation was a necessity to survive the long winter in most locations. Over the centuries, many have gotten their winter produce fix from a simple non-tech solution: the root cellar.

Last year when I did my One-Month Stockpile Challenge, I realized that this was a glaring omission in my food stockpile process, so this year, I’m determined to add this strategy to take my stockpile to the next level. Fall is the perfect time to begin because for the next few months, those hard-shelled root vegetables as well as items like apples and potatoes, will be abundant and cheap.

The first root cellars in recorded history were in Australia – 40,000 years ago it is indicated that they were burying their yam harvests in order to keep them fresh. Since then, underground food storage caches have been found all over the world, as people took advantage of the cool moist atmosphere a few feet down.

THE IDEAL ROOT CELLAR

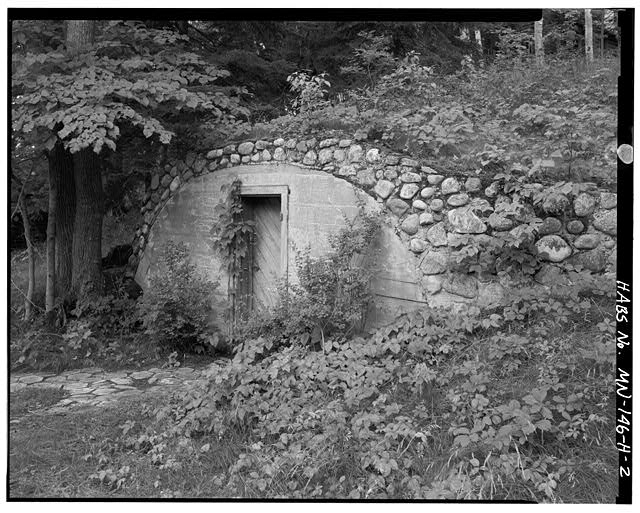

Root cellars are often in the basement of one’s home or in a separate concrete or stone cellar just outside the home. Michigan State University offers these tips on conditions for the ideal root cellar:

The produce is still alive – stored carbohydrates of energy is consumed in the presence of oxygen and produces heat and carbon dioxide. To maintain the proper “living” conditions, at least three variables need to be considered: temperature, humidity and ventilation.

Temperature:

Most cold tolerant or cool season crops will store best between 33 and 35F or just above freezing and up to 40F. Warm season crops sensitive to chilling injury (tomatoes, cucumbers, etc) are typically stored at temperatures above 50F unless processing, cooking or eating will occur shortly after removal from storage. The temperature needs to be actively monitored and managed and will vary with the quantity of produce in the space.

Humidity:

Most root and leafy crops will store best at high humidity (+80%) or moisture levels. Root crops like carrots need to be stored in some moist medium to maintain quality. Some crops like onion, garlic and winter squash store better at low humidity level (less than 60%). Moisture may need to be added by wetting the floor or walls with water depending on the construction methods.

Ventilation:

Reasons for ventilation include: 1) removal of heat of respiration, 2) replenishing the oxygen supply, 3) removing volatile compounds from the produce that may effect flavor or sprouting like ethylene. The greater the density or amount of produce in the space, the more ventilation is needed. Ventilation or air tubes need to be planned prior to construction and place during construction.

Common storage categories are 1) cold dry, 2) cold moist, 3) cool dry, 4) cool moist. (source)

The University of Alaska Fairbanks Cooperative Extension Service in cooperation with the United States Department of Agriculture offers the following chart with storage information for specific produce:

| Vegetables | Temp F. | % Humidity | Storage Time | Comments |

| Beets | 32° | 90–95 | 3 months | Leave 1-inch stem. |

| Brussels sprouts | 32° | 90–95 | 4 weeks | Wrap to avoid drying |

| Cabbage | 38° | 90–95 | 4 months | Late maturing varieties ** |

| Carrots | 32° | 90–95 | 5 months | Top leaving ¼-inch stem * |

| Cauliflower | 32° | 85–90 | 3 weeks | Wrap in leaves * |

| Celery | 32° | 90–95 | 4 months | Dig with roots *** |

| Chinese cabbage 32° | 90–95 | 2 months | Dig with roots *** | |

| Cucumbers | 50° | 85–90 | 3 weeks | Waxed or moist packing * |

| Kohlrabi | 38° | 90–95 | 3 months | Trim leaves * |

| Onions | 32° | 55–60 | 8 months | Dry for two weeks. |

| Parsnip | 32° | 90–95 | 6 months | Top leaving ¼-inch stem * |

| Potatoes | 38° | 85–90 | 8 months | Pack in boxes unwashed. |

| Squash | 60° | 55–60 | 3 months | Winter types, leave 2-inch stem |

| Tomatoes | 60° | 55–60 | 8 weeks | Single layer in covered boxes |

| Turnips | 38° | 90–95 | 3 months | Waxed or moist packing * |

| Small fruits | 32° | 85–90 | 7 days |

* Pack in moistened sawdust or sand.

** Wrap in clean newspaper.

*** Replant in moist sand.

(source)

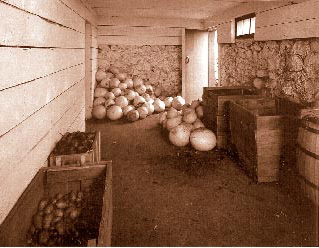

ORGANIZATION OF YOUR ROOT CELLAR

You can’t just place everything together and hope for your food to all remain fresh. Some items cannot be stored together because they release a gas called ethylene. Ethylene gas is a ripening agent,which hastens the decomposition of other produce.

For example, apples, pears, and tomatoes produce high amounts of ethylene and should be placed higher than other foods, and near vents if possible. They should not be placed near potatoes and carrots, as the ethylene will cause those to spoil rapidly.

Some produce will easily absorb odors from items with strong smells. Strong smelling foods like cabbages or turnips can be wrapped in newspaper to help contain the smell. Onions store well when hung in mesh bags.

Some produce is stored more successfully if cured at a temperature of 80-90 degrees F for 10 days before being placed into storage:

- winter squash

- onions

- potatoes

- garlic

Two small investments for your root cellar should be a thermometer to measure temperature and a hygrometer to measure humidity. This way you can ensure your conditions are right to keep your food fresh for the longest possible time.

Resources

The following resources provide specific information on how to create and maintain your own root cellar:

Root Cellaring by Mike and Nancy Bubel

https://www.theorganicprepper.ca/how-to-create-a-root-cellar-for-food-storage-09142013

Please feel free to share any information from this site in part or in full, giving credit to the author and including a link to this website and the following bio.

Daisy Luther is a freelance writer and editor. Her website, The Organic Prepper, offers information on healthy prepping, including premium nutritional choices, general wellness and non-tech solutions. You can follow Daisy on Facebook and Twitter, and you can email her at daisy@theorganicprepper.ca

It’s $1.99 as of the time of this article…