Wind, sun or hydro – its the future Could urban communities make their own electricity, and even sell surplus energy to their neighboring communities?

The South African Council for Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) has been pondering this question in a R20m pilot project involving the establishment of two standalone mini-grids that generate electricity from renewable energy resources in rural areas.

The project was launched by the CSIR and Shell Solar in 2002 to build a database for the development of a business model of commercially viable mini-grids in areas which do not have access to electricity from the national grid. That normally means rural areas, but in South Africa increasingly it could be anywhere.

Also known as hybrid-grids, mini-grids are based on harnessing renewable energy resources available in a specific area. These range from wind to solar and hydro energy, and biomass such as plant material that can be converted into liquid or gaseous forms of energy. Waste plant material and fuel wood are the most basic sources of biomass energy. But other forms include ethanol gel produced from certain crops and methane gas extracted from animal waste or landfills, which can be converted into electricity.

The DME pilot project was undertaken at Hluleka Nature Reserve on the Eastern Cape Wild Coast and at the nearby village of Lucingweni, both of which are not connected to the national grid.

Two small turbines and an array of photovoltaic (PV) panels to convert solar energy into electricity were installed at Hluleka to supply power to the nature reserve’s 12 bungalows and its administration office. Solar water heaters were installed together with liquid petroleum gas to provide supplementary heating and cooking energy.

At Lucingweni electricity was supplied to 220 households via six wind turbines and an array of PV panels. From a technical perspective the systems performed as designed, says Steve Szewczuk, research group leader for Rural Energy & Economic Development in the CSIR’s Built Environment division.

However, DME budgeted only for the installation of the systems. With no additional funding available for operating and maintaining the installations, they gradually fell into disuse.

The DME is now considering a report drawn up by independent consultants who have analysed the outcomes of the projects to make an assessment on whether they could be replicated elsewhere on a commercially viable basis.

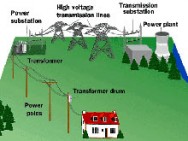

Meanwhile, with Eskom’s coal-based electricity price rising sharply and amid fears of power shortages for the next five to seven years, the CSIR has been looking at the possibility of extending the mini-grid concept to urban areas where they can be used to supplement power from the national grid. The concept is known as a distributed or decentralised electricity generation system.

As renewable energy technologies improve and their usage makes them more affordable through economies of mass production, says Szewczuk, it is conceivable that gated communities, large office parks or whole suburbs could develop onsite electricity. They could do this mainly through the use of various forms of solar energy and conversion of waste material into biogas, but other emerging technologies could also come into play.

The CSIR, together with Eskom and the DME, is creating an off-grid electrification planning tool that could be used to develop business models for the implementation of mini-grids for rural areas. It is conceivable that such a planning tool could be extended to urban areas, says Szewczuk.

Work already done includes refining a US developed software package known as Homer, which incorporates a Geographic Information System (GIS), to help developers to configure the most optimal use of renewable energy sources in a given area. The CSIR has incorporated a wide range of SA data into the package so that it can be applied in this country.

Much discussion is taking place on what should happen next. But Szewczuk says the ideal outcome would be a pilot project that could demonstrate the usage of appropriate technologies in an urban environment.

Communities in developed countries are already showing what can be achieved. The German town of Freiamt, with a population of 4300, is generating much of its electricity through a combination of wind turbines, rooftop PV panels, small-scale hydro power, and biogas.

The little Black Forest town even produces electricity surpluses, which it sells to the national grid. The Danish island of Samsoe is producing most of its electricity from wind turbines.

Energy Alternatives: Cool Fuel Roadtrips Wind and Micro Hydro Power