The Australian city of Sydney is making the first moves to ending its reliance on centralized energy.

It is putting into place a network of tri-generation plants that will eliminate the need for council buildings to rely on coal-fired power generation and could, ultimately, take the entire city off-grid.

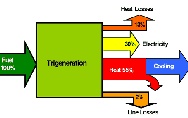

Tri-generation plants generate electricity usually through a gas-fired turbine (although it can be biomass or other sources) and uses the excess heat for heating and airconditioning.

The gas fired plants produce both electricity and heat and can transform some of the heat into cooling energy as well.

The Council’s chief development officer for energy and climate change, Allan Jones, says remote coal fired power plants are inefficient because they produce twice as much heat as they do electricity. “You lose another nine or ten per cent of electricity in the grid. So by the time the electricity actually reaches your home, you’ve only got less than a third of the energy that was burnt at the power station.

“With co-generation or tri-generation or decentralised energy, you generate that electricity and the waste heat that’s generated is recovered and then put into heating buildings, providing hot water. And through tri-generation we can convert that hot water into chilled water through air conditioning and refrigeration which is of particular benefit for a city like Sydney.”

Other countries are already well ahead of Australia which currently generates about 9 per cent of its energy from local sources. It’s cooler countries like Denmark, Latvia and the Netherlands that lead the way in distributed energy,largely because earlier co-generation plants produced electricity and heat. It’s only quite recently that we’ve been able to come up with economic ways of using that heat to actually cool our buildings. So that’s why you’re starting to see tri-generation in Sydney and other parts of Australia.

The struggle now is to make tri-generation financially viable. Alan Pears is an environmental consultant and an adjunct professor at RMIT. He says the current regulatory environment favours larger infrastructure and does little to encourage other forms of power generation.

“Our energy regulatory framework is Energy Network’s monopoly power which they then exert over competitors such as tri-generation,” said Pears. “Also the way the regulators have traditionally structured the pricing, so, in terms of their financial rewards to a network, has favoured this traditional, centralised approaches and investment in energy network capacity rather than investment in distributed generation.”

So, this is a very powerful set of factors.Many building developers and owners have scrapped or scaled back plans for tri-generation plants because it wasn’t profitable to sell power back to the grid. Allan Jones says it’s a problem that Sydney City Council is grappling with as well.

The city project will establish tri-generation plants in seven locations around the CBD at Town Hall, Customs House and its five aquatic centres. The plan is to create a network of such plants providing up to 325MW over a 15-year period, which could connect to neighbouring buildings and the entire CBD.

Jones, who took the English city of Woking off the grid and implemented similar plans for London, is now Sydney council’s chief development officer for energy and climate change. He says there are numerous advantages to the plan. It will cut emissions by about 70 per cent, reduce and possibly eliminate the need for new coal-fired baseload generators and eliminate losses from transmission.

The City of Sydney is the first in Australia to undertake such an ambitious project, but the concept is not new. The very first power station built in Manhattan in 1882 by Thomas Edison was a co-generation plant and the island has been largely powered by a network of co-generation and tri-generation plants ever since. Jones says Edison was a great believer in decentralised energy and hated the idea of wasting excess heat. Sadly, the systems that came to dominate most national grids focused on a centralised business model, ignoring the waste heat.

But now it’s back to the future — just like the car industry, which seems destined to return to the electric vehicle, which was only supplanted by the internal combustion engine because it was easier to create a network of fuel pumps than charging stations at the time. For the City of Sydney to achieve its ambitions, however, it will require modifications to regulations that would allow it to generate energy and trade within its own network of council buildings and to third-party buildings.

INTERVIEW FROM ABC RADIO July 2008

In the early 1990s engineer Allan Jones set the town of Woking on the path of independence from the national grid. It was a move that saved customers money and radically reduced carbon emissions. He is now trying to repeat the same success for the City of London. Could it work in Australia?

HIDE TRANSCRIPT

Transcript

Geraldine Doogue: Well even if you closely examine your electricity bill next time it comes around, you probably won’t grasp what that simple kilowatt per hour actually measures, because it won’t show you how much electricity, say, is lost in transmission, or payments between companies and so on. That the actual amount required to heat and cool your home and for cooking and so on, is a much smaller proportion than you might imagine, because it’s all too remote from the local area where it’s used.

At least that’s the view of my next guest, who’s one of those roll-up-your-sleeves engineers who was aware that there was much energy to be saved in this humble household zone and the businesses around them. And he put this into practice in a south of England borough called Woking, during the 1990s, which takes in the commuter zone of Surry. He helped the council save almost 80% of their energy during the ’90s and up till 2004.

Allan Jones has been a guest of the City of Sydney this past week, and he’s been wowing audiences with his matter-of-fact presentations delivered at pretty fast speed I can assure you, having heard it, about what’s possible right now. He says, by the way, that it’s only when you start doing emissions reductions rather than talking about doing them that the whole politics starts to shift and boy, do we need to think about that right now in Australia.

Anyway, I’ll let him tell us how he persuaded this suburban borough to bring about these changes and how he’s adapting them to his latest job as CEO of the London Climate Change Agency. Good morning Allan, and welcome.

Allan Jones: Good morning.

Geraldine Doogue: So what did you propose to the good burghers of Woking back in the early 1990s?

Allan Jones: Well that was in 1990 where we were undertaking an environmental audit and, as a senior officer in council, I took the opportunity to submit a report on global warming, which was two years before the Rio Earth Summit, so this was a completely new topic for the councillors. It was a flyer really, I didn’t really expect much more to happen with it. But that was July 1990, and by October the same year, which is pretty fast going for any public sector organisation, we had the Energy Efficiency Policy in place and a revolving fund, and all that Woking has achieved over the past years started from those very humble beginnings.

Geraldine Doogue: And what was it? What did you suggest? How did you suggest they could reduce their footprint?

Allan Jones: Well the primary cause of climate change is centralised energy, about 75% for a city.

Geraldine Doogue: And what do you mean by centralised energy?

Allan Jones: That’s your big power stations, and essentially the reason why that is the case, and coal is the most polluting, gas is the cleanest of the fossil fuels, but coal’s about five times more polluting than gas and, more importantly, for every unit of electricity they generate, they generate two units of heat, and the heat is thrown away for the cooling towers. And also in the UK, 50% of our water resources is used to reject that heat. That will probably be more here in Australia because you have a hotter climate.

Geraldine Doogue: So just getting back to this issue of centralised energy, so you diagnosed, with your engineer’s hat on, that centralised energy was not the most efficient way to go. What did you actually tell the people in Woking they could do instead?

Allan Jones: That was to generate energy locally. And we call that combined heat and power, so instead of throwing that heat away, you can recover that heat and use that for heating buildings, providing hot water, and using a technology called heat fired absorption cooling. We can even generate chilled water for airconditioning and refrigeration.

Geraldine Doogue: So this is your co-generation that you talk about, combined heating and power

Allan Jones: That’s right. Co-generation when it’s heat and power, and if you have cooling, like you have here in Australia, then we would call that tri-generation.

Geraldine Doogue: So effectively, you were using the energy that came from the national grid again, were you? Like you didn’t remove yourselves from the national grid, did you?

Allan Jones: Well physically we were still connected but we didn’t make any use of it. We didn’t go around cutting any cables or anything like that, we just embedded the combined heat and power systems and renewable energy into the local distribution network, not the national grid, into the local distribution network. And from there we supplied electricity locally and also heat and cooling to various buildings, commercial buildings, residential customers and so on.

Geraldine Doogue: How much did it cost to convert then to put these systems in?

Allan Jones: Well money was obviously spent in capital to actually build the systems in the first place. But a little-known fact, and if you look at people’s energy bills, we were actually able to extract the real economics of these green technologies simply by not supplying the grid, so we did not supply our electricity to the grid, we supplied it directly to consumers, and because of the regulatory barriers, the regulatory system is designed for remote power stations, we actually laid our own cables, private wire networks they’re called. Which if you look at your electricity bill, you don’t see this on your electricity bill, but it’s made up of a number of charges. Electricity is only about 20%, 25% of your electricity bill. You’ve then got transmission and distribution losses and customers have to pay for that, and they’re probably totally unaware of that, but they have to pay for it. In the UK that’s US$1 billion worth of electricity is lost every year just heating up the wires and the transformer exchanges. Australia will be even higher in that because it’s a much bigger country.

Geraldine Doogue: So it just goes into the ether?

Allan Jones: Just heats up the wires, which is energy that’s lost. You also have the national grid charges, what’s called a transmission use system charge, that’s for transporting electricity from the remote power station to the grid supply point. Then your local electricity company charges what’s called distribution user system charge, for transporting the electricity from the grid supply point to the end consumer. And then the government adds all its taxes and levies to that.

So what we did in Woking and what we’re now doing in London is that—and one of the reasons why these green technologies appear to be uneconomic is because they’re treated as if they were remote coal fired power stations, and to give an example of that, if you had a solar energy system on the roof of your house and you were exporting surplus electricity, the laws of physics dictate electricity will always flow to the nearest point and so that would only go to your next-door neighbour. Yet the energy trading system would treat you as a coal-fired power stations hundreds of miles away and would add all those transmission distribution losses and charges to that. So somebody else makes the profit out of that.

So what we simply did in Woking was just to cut out those middle men and supply people directly. We were able to undercut the grid, we supplied energy at a lower price than you can get from the grid, and we increased our economics by about 400% simply because the retail prices is about four times that of the wholesale prices.

Geraldine Doogue: But it just sounds like an immense amount of expenditure to lay all the requisite systems in place to make a localised grid. How much did it cost Woking?

Allan Jones: With the electricity network, it was relatively cheap. The main cost of these systems is in the combined heat and power system itself and the district heating network, and whilst you’ve got the trenches in place when you’re putting in the district heating, to drop a cable in the same trench is next to nothing.

Geraldine Doogue: And that cable supplies the heating?

Allan Jones: No that cable supplies electricity directly to consumers and the heat supplies either heating or cooling.

Geraldine Doogue: And this is gas-fired or coal-fired?

Allan Jones: Initially we started out with gas-fired, and as I explained before, if you want to get big reductions in CO2 emissions you want to hit the ground running, then natural gas is so much cleaner than coal and oil and those other fossil fuels, so you will get huge reductions in CO2 emissions just by changing the fuel, but even bigger reductions by recovering the heat. Two-thirds of energy’s wasted at power stations. More recently we’ve been looking to generate our own renewable fuels and waste is the area that we’re looking at. The amount of waste that’s currently going to landfill in London could be converted into renewable gases.

Geraldine Doogue: Now just because I think it’s hard enough coping with co-generation and tri-generation, before we get to converting waste, some European countries go one step further I think than Woking and they practise this tri-generation, particularly the Danes. Now what does that involve?

Allan Jones: Well, actual facts, Woking has more tri-generation than Denmark has. I was the first person to actual instal tri-generation back in the early ’90s.

Geraldine Doogue: And what is it?

Allan Jones: That was copied by the BBC—so we expect the ABC to do something similar!

Geraldine Doogue: Now tell me what it is? What’s tri-generation?

Allan Jones: Well tri-generation is combined heat and power and the heat is used through an absorption chiller which converts the hot water into chilled water and that’s how you get air-conditioning. Now that has a big impact on reducing emissions because it displaces electricity you’d otherwise use for conventional air-conditioning. And in Australia probably a large part of your electricity bill is for air-conditioning. It generates more electricity, more low-carbon electricity from the heat-to-cool process because your combined heat and power system will be much bigger now, because it’s not just supplying heating and hot water, it’s supplying cooling as well. So that’s why in the London plan, any new development cannot gain planning consent unless it fits a tri-generation system, plus 20% renewable energy.

Geraldine Doogue: Allan Jones is my guest here on Saturday Extra. He’s the chief executive officer of the London Climate Change Agency, and we’re talking about what emissions savings methods he’s already put into place in the borough of Woking and now into London. Okay, so I just want to get a couple of things clear. So the borough, the council, spent the money to effectively cable, I suppose, outside people’s homes, was it mandatory? Like did people have to sign up to this?

Allan Jones: Oh no, no, it was voluntary. And it’s not difficult to get people to do that if you’re supplying them with cheaper energy.

Geraldine Doogue: So how much did their energy, did the average household say, their energy bill come down over the period?

Allan Jones: The average household saved in the region of 130 pounds to 200 pounds a year.

Geraldine Doogue: And the borough, were they driven by any emissions trading targets, like was this totally separate to all cap and trade schemes?

Allan Jones: This is absolutely nothing to do with emissions trading, this is about getting on and doing it. You cannot tackle climate change by trading, you have to actually do things.

Geraldine Doogue: I want to go back. Did the borough have to borrow money in order to lay all this new infrastructure?

Allan Jones: No, that came from the revolving fund. Essentially, this is what I was talking about earlier about my global warming report, because they said ‘That’s great, we’d like to do something; what do we need to do?’ I said, ‘First of all you need to establish some targets, what you think’s achievable’. And we agreed that they would do so without asking how much that was going to cost. So sort out the politics, sort out the targets and so on. And at the next meeting I then came forward with how it could be funded.

I obviously needed more money than what I was asking for so I basically had a five-year target initially and I asked for a fifth of the money, I said, ‘Providing you allow me to recycle the financial savings from the reduced energy bills, I won’t need any more money from you.’ And that was started with a quarter of a million pounds. And it had no further impact on the council, and the council’s saving something in the region of 1.2 million pounds a year on its energy bills.

Geraldine Doogue: How many householders in Woking?

Allan Jones: About 37,500, a population of about 100,000 people. And the money that they earn from their joint venture energy services company which I established later in the late 1990s, far exceeds that as well. So from an economic point of view Woking’s done very well out of tackling climate change.

Geraldine Doogue: A lot of tenants in your average office building can’t get a broken tile fixed, let alone a whole new energy system. How do you draw small office towers for instance into this, because that is not their core business is it, energy. I mean it might be the big developers, but it’s certainly not the small people.

Allan Jones: You’re absolutely right. In London we established a better buildings partnership, which brought together these really, say, the top 20 large building owners and most of whom are property developers as well. They’re keen to tackle climate change, they’re being put under pressure by tenants who are now asking what is the energy performance of their buildings and so on, which now have to be rated in London. And as a consequence, if you can get the big property owners, the big landlords on board, it’s then much easier to get the smaller tenants connected because it’s being driven by the really big tenants.

Geraldine Doogue: So the big tenants, they are the ones, are they, who together with say the London Climate Change Agency, it’s a public-private partnership, they lay these new systems, is that the idea?

Allan Jones: No, what we did in order to make this easy for people, we established an energy services company, and the purpose of the energy services company is to design finance, underline finance, build and operate decentralised energy systems, so make it easy for developers. So basically they join in partnership to supply their new development or existing development as the case may be. Now two years ago there was not an ESCO market in London. I established an energy services company in Woking, which is how that was able to accelerate to over 80 decentralised energy systems, but because it’s London, London is 75 times bigger than Woking, I put that out to competition. I had nine major energy and utility companies tender for that to become the private sector partner in the London ESCO, including two international oil companies and a large American energy company, and the six major utilities in the UK. EDF Energy won that tender and we established a London ESCO.

Geraldine Doogue: I know you’ve been to a couple of workshops and events in Australia and you’ve been exposed to our interests and worries. One man, for instance, talked about the looming argument in Victoria about what’s called third party entrants in energy provision being banned, and this whole issue hasn’t even begun in a place like New South Wales. So I mean how did you get around that? Regulations and existing energy companies clearly wouldn’t have welcomed this would they—because you’re taking their business away?

Allan Jones: If you’re an energy company, this either represents a threat to you or an opportunity. So the smart ones see it’s an opportunity. I mean EDF is one of the largest energy companies in the world, and they saw it as an opportunity. If you’re an energy dinosaur you can either remain an energy dinosaur and become extinct or you can move forward in the new 21st century to how you need to supply these systems. You cannot tackle climate change without tackling centralised energy because in London for example it’s responsible for 75% of London’s CO2 emissions. We tend to smear that across end use and say housing’s responsible for a proportion of it, industry, commercial, but actually those emissions have already been released into the atmosphere before you’ve turned your light switch on.

Geraldine Doogue: But those centralised energy companies are much smaller, aren’t they, if you’ve saved 77% of energy, they’re simply not selling the same amount of product.

Allan Jones: Energy in a different place. Instead of it being generated remotely, it’s now generated locally, which gives you the opportunity to recover the heat to either heat or cool buildings. In actual fact it’s a much more efficient system, it uses two-thirds less fuel because you’re not burning fuel to throw it up into the atmosphere, doesn’t consume all that water, which is a big issue for countries that suffer from drought, and because you’re not throwing heat away you’re not using water to throw that heat away, you’re actually using that to provide low carbon and eventually zero carbon energy supplies.

Geraldine Doogue: And you think it could adapt to Australia, do you?

Allan Jones: Absolutely.

Geraldine Doogue: And it would shift the politics, the doing of this?

Allan Jones: Well we’ve already seen the city council taking the lead in this area with their 2030 vision. If Sydney takes the lead in this in the same way that London has, and that’s the reason why we set up the C40 to get these big well cities to actually copy what London does, then that can actually have an influence. And this year in South East Asia we’ve seen some movement in South East Asia, and particularly Malaysia, and eventually I believe China and India. That could be the leading world city in this part of the world in the same way that London’s leading the way in Europe.

Geraldine Doogue: Allan Jones, thank you very much indeed for joining us.

Allan Jones: Thank you.

One Response

Allan Jones: This is absolutely nothing to do with emissions trading, this is about getting on and doing it. You cannot tackle climate change by trading, you have to actually do things.

Brilliant.