If you are a smallholder who wants to apply for your carbon credits, get in touch with us at off-grid.net, or leave a comment at the end of this story. We will collate all claims and submit them when there are enough to qualify.

In Britain, for example, farmers have two options – go green or go under. The calculation is simple – A farmer plants a wood, grows bigger hedgerows or tends the soil in a certain way, that sucks a certain number of tonnes of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

This is verified and the farm is then granted a certificate for how much CO2 it has absorbed, which can be sold to a business that needs to reduce its own carbon footprint.

The UK is not alone in this field, with similar initiatives under way in the US, the EU, Australia and New Zealand.

In eastern Australia, a vast area called the “mulga belt” is now home to a booming carbon trading industry that has netted 150 businesses at least $300m in less than a decade, according to official figures reported by the Washington Post.

Businesses should be looking to reduce their own emissions first, say experts, but carbon credits could help with any residual emissions, the ones that are difficult or impossible to remove.

Farms and landowners are well placed to help with this, as many actions they can take to improve their own operations will also cut carbon emissions.

Farmers can apply for carbon credits if they plant their fields with environmentally-approved crops. Small growers cannot. The amount seems small, only a £100 per Hectare in the UK and £168 for woodland, but to someone with a two Hectare smallholding who survives perfectly well on £10,000 a year, its a 2% pay rise, for doing what they were going to do anyway.

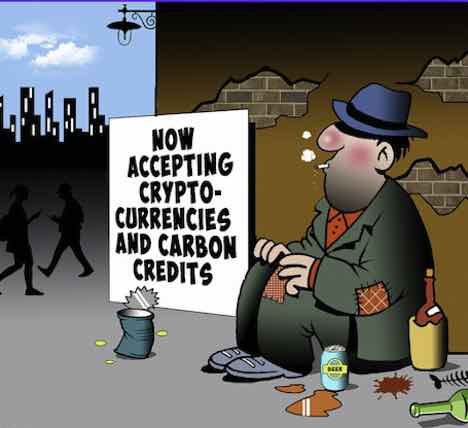

At the moment, UK farmers cannot participate in the British emissions trading scheme, although this may change soon with the Government having recently consulted on proposals to bring them in. But there is nothing to stop us all, every landowner, garden owner and allotment owner who wants to log-in to any online application form set up for farmers.

In the meantime, farms and others can participate in voluntary carbon trading markets. The two most established are the Woodland Carbon Code and the Peatland Code, both of which are recorded on the UK Land Carbon Registry.

The woodland code rewards landowners for planting trees, typically over a typical period of 30 to 40 years. It had 1,825 projects registered at the end of last year, with an average size of only 35 hectares, according to statistics published on its website. These have stored, or “sequestered” in industry jargon, around 21.7 million tonnes of carbon dioxide.

But when I planted 250 trees on my pasture, how many carbon credits did I receive? Zero. Zip. Nada.

Pre-internet it was justifiable to argue that the cost of administering a scheme like that would outweigh the payments being made. But Google Earth and digital data have slashed the time and cost involved.

Other codes being developed would establish similar regimes covering soil, hedgerows and saltmarsh, as well as natural habitats that also store carbon dioxide.

In Australia’s Muga belt, Nature-based voluntary carbon credits were worth an estimated $3.4bn (£2.9bn) in 2022, according to data collected by advisory company Climate Focus. And by 2030, McKinsey predicts the global carbon credits market could be worth $50bn a year – with nature solutions representing up to 40pc of the total.

Under the emerging soil carbon scheme, it is estimated that UK farmers could earn £200m to £750m per year from selling carbon credits across 17.7 million hectares of land.

That is based on an assumption that 1-2 tonnes of CO2 could be sequestered and stored per hectare, at a price of £11 to £21 per tonne (or up to £42 per hectare).

Returns under the woodland scheme are a bit better, says the Financial Times. For planting one hectare of native woodland, storing 6 to 8 tonnes of CO2, a farmer could receive up to £168 per hectare under the same price range.

But many experts believe prices will go far higher than this in the coming years. According to the International Energy Agency, prices will need to reach $130 per ton by 2030 and $250 per ton by 2050 in order for the industry to work.

These markets are still grappling with a host of regulatory and ethical dilemmas. Many voluntary carbon trading schemes remain opaque and use a variety of different standards – making it hard for businesses to know if they really count towards emission reductions. A code for smallholders would give them a much stronger case than industrial scale farmers or woodland owners.

For farmers, investing in changing practices is also a costly affair – and committing to a long-term contract today at low prices is hardly attractive. But most smallholders are already carrying out the processes required by carbon monitors.

If you think food and wood production should be rewarded with carbon credits, comment below this article.