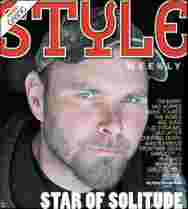

Tim Barry has been rockognised.

The singer songwriter from Richmond VA lives back of his girlfriend’s house in a shed with a busted kerosene heater – not great at this time of year, but ok, really, when you are wearing camouflage coveralls to fight the chill.

Winter has been harsh but the shed balances Barry’s queasy relationship with fame. Since the early ’90s, he’s fronted the speed ’n’ scream punk rock band Avail, but he isn’t always as comfortable with the attention.

He’s a hermit with a publicist.

WELL-ORDERED bookshelves run along the back wall of the shed. Barry has stocked them with counter-culture literature and a row of thick, black, hardbound journals that he’s meticulously kept through the years. Unlike most journals, these are semi-public records. In them he’s pasted photographs and show fliers, set lists, an e-mail from a fan stationed in Iraq and logged his own reflections on the times.

There are pictures of people who have his lyrics tattooed into their skin. “Ride fast, live slow,” is a popular choice. He’s always welcomed people to paw through the journals, says A.C. Thompson, a close friend who writes the liner notes for Avail and all of Barry’s solo work.

Barry’s shed is immaculate. To the right of the shelving sits his neatly made bed. To the left he’s built a stall where he relieves himself into a bucket of sawdust below. He’s nailed to the wall a framed picture of three of his best friends, Travis Conner and Ronnie Graham standing arm-in-arm with a man called Weezle, the boys’ 73-year-old role model for off-the-grid communal living in Old Fort, N.C. Perhaps, surprisingly, Weezle is the only one of the three still alive.

Barry grew up in Reston, where his parents sang in the church choir. His mother played folk music at home and his father played classic rock in the car. Otherwise the family didn’t go out of its way to emphasize music. But something must have stuck. Barry’s older brother, James, composes avant-garde music and Caitlin, Barry’s younger sister, plays violin and accompanies him on tours and on his records.

When fans recognize him in the grocery store he calls it getting “rockognized.”

Tom Breihan saw Avail for the first time 15 years ago and still regards it as the best show he’s ever seen. Now a staff writer for the influential music magazine “Pitchfork,” he says “if you cared about punk rock and hardcore you pretty much regarded this band with a religious sense of awe.” Their music mixed “classic swampy southern rock and scream in your face hardcore. It made intuitive sense at every moment. And live they were just a supernatural force.”

At first, Barry was terrified of performing alone and unplugged. To acclimate himself into his new role, he embarked on a low-key European tour and released his first solo CD on a small German label.

To keep his head on straight between tours he worked volunteer jobs with local services groups, such as the now defunct Grace House and Food Not Bombs. Through the music scene he met Ronnie Graham, a freewheeler who pulled out of dumpsters or stole most of what he owned, but would share whatever he had. Graham introduced Barry to riding trains — illegally hopping into CSX boxcars and seeing how far you could go. A transient uncle had taught Graham rail-riding etiquette.

Riding trains offered speed, solitude and breathtaking beauty. It brought Barry adventure and clarity in the down time between tours and eventually blossomed into a defining obsession. He can tell you which freight trains roll through what yard and where they’re headed. Trains started showing up in the music.

Riders often write on trains with grease bars, usually a personalized doodle that stays the same and a quote that changes so that people know who you are and what you’re up to. “Ride fast, live slow,” was one of Graham’s lines.

On his new album songs feature first-person appearances by Iraq War amputees, hobo junkies and a brother who takes the fall when his sister shoots her abusive boyfriend. He tells the story of Gabriel, a historical short about Virginia’s failed slave uprising, tapping into the local angle — the slave was hanged and buried near or under what is now a parking lot at 15th and Broad streets. The Gabriel song has proven to be the crossover hit on this album, and Barry received invitations from high-school history teachers and to a family reunion for Gabriel’s descendants (the lyrics ran in the program). The songs also commemorate, in slow motion, a hanging much closer to him.

FALL 2007, his pal Conner was in a bad way. He went missing for a few days in November, but resurfaced to everyone’s relief. He had Chinese food on Christmas Eve with his girlfriend. He hit the trains pretty hard, tagging “Going on Ahead” under all his characters. At 5:10 p.m. on Jan. 11, 2008, Barry got a text message from Conner. “Going on ahead,” it says. “Meet you there. I love you brother.”

Barry freaked. He rushed to Conner’s apartment, but Conner wasn’t there. Of all of his favorite secret spots, there’s one Barry had never been to, a place in the East End he called Fort Solitude. Barry wasn’t sure he could find it, wasn’t sure he could get out there in time. He called Kiesler. She finally showed up. It was getting dark. They took a guess at where the spot might be. Kiesler pulled over by a rail line near some woods. Barry told her to stay in the car and lumbered off into the forest. Sooner than he expected, he found Conner.

Later, Barry would record in his journal the following: “Travis had in his pockets his cell phone, scrap paper, with moniker quotes crossed off, a digital camera and a receipt for rope bought at Lowe’s.”

Somehow Barry made it back to the car. Somehow they called the police. For a horrifying smear of time, the incident had to be treated as a possible homicide until the officers found the suicide note Conner left at his apartment. Then they had to go find his girlfriend, fish her out of the restaurant where she worked and tell her the news. Barry and Kiesler were hosts of a party after the funeral. Some say it was the best party for the worst possible reason.

Barry became scared of the dark, so he couldn’t soothe himself with any of his forest retreats or late nights and early mornings. He decided to get out of Dodge and visit his old rail-riding friend, Graham, who was living in Asheville, N.C. — settled in for the first time. After about a month of living in Graham’s basement, Barry accepted an invitation to tour manage a Richmond band, Smoke or Fire. He left Ashville and joined the band on the road.

Two days later, Graham, the man who introduced him to riding trains and gave him one of his signature lyrics, died in a bicycle accident. Barry turned around and went right back to Asheville to try to raise money for the funeral. He got the dates of Conner and Graham’s deaths tattooed on the insides of his middle fingers.

The former leader of Avail recorded his most recent solo album, “28th and Stonewall,” at Minimum Wage studio with longtime collaborator and co-producer Lance Koehler.

“Fifteen, 20 years ago he would have said, ‘Fight the power,’” Thompson says of Barry. “Now there’s this profound understanding that we only get one shot, that we have to love one another, that we have to be compassionate. And how you behave while you’re here and how you treat people is incredibly important.”

Barry’s attitude may have changed, but physically he wasn’t so hot. In 2008, touring for the “Manchester” record, he played 54 shows in 58 days, a grueling schedule. He had cramps, had to urinate all the time. His body would go numb, he lost 20 pounds. Kiesler walked into a South Carolina club to meet up with him at the end of the trip and didn’t recognize her boyfriend. “I had my peoples die,” he said. “Death was following them, maybe it’s following me now too.”

The day after Barry got back to the shed, he collapsed on the floor. When he came to, he drove himself to St. Mary’s Hospital where the doctors told him he was days from death. He had developed Type I diabetes, the form usually found in children. The great historian’s personal history very nearly ended there.

He plotted a methodical recovery, adjusted his diet and stuck to Miller Lite. He learned how to manage his insulin at home, then on tour, then on trains. He wrote his new album, “28th and Stonewall,” in three weeks. The track with the brass band sticks out. The song is called “Will Travel,” the name Conner gave to a run of self-published photography zines. Between the wailing trombone solos and twinkling high-hats of a New Orleans-style jazz funeral, Barry has published a posthumous edition of his friend’s journal in song, describing images of a freight-train hopper’s heaven. “I know a train yard that ain’t got no bull,” he sings. “Where the car knockers serve you three hot meals, send you off with cigarettes, weed and booze.”

Tim Barry’s journals serve as a kind of punk-rock-ipedia, informed by politics, art and subcultural lifestyles.

In a journal entry from right before Conner’s death, Barry copied a quote from the Vietnam War-novelist Tim O’Brien: “Stories are for eternity, when memory is erased, when there is nothing to remember except the story.”

Perhaps the surest sign that all this tragedy hasn’t taken the fight out of Barry comes in an e-mail dispatch while on a solo Canadian tour. “Just out of the hospital — Canada style,” writes Barry, the survivor. “12 to 8am in e-room. Broke my hand on some dude’s head last nite … onstage. Not sure how I will play. Show’s sold out. Yay.”

One Response

Just when I was taking more of my music in the commercial direction, Barry hits hard with the need for more truth. Guess I’ll get more used to “less of the glam” and more of the tram. Love his sincerity, pain = gain.

To all the truth seekers.