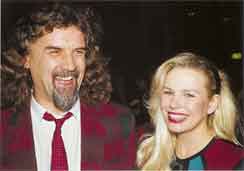

Dropping out – Stephenson and Connolly

The wife of comedian Billy Connolly has revealed the couple might stay off-grid forever after she achieved her dream of sailing the world for a year.

Pamela Stephenson, 55-year-old psychologist and former comedienne, who has three children with the Big Yin, said she was sick of being the “responsible one” and was desperate to escape her humdrum existence.

So she embarked on a mid-life adventure which saw her sail 19,000 nautical miles in ten months, visit uncharted islands and resist a hunky fisherman. But this was no primitive idyll. She travelled in a 112ft super-yacht with a crew of seven.

She has written a book on her travels, Treasure Islands, which she says has helped put her life in order: “I’ve survived. And I’ve never been so terrified.” You can buy the book on the next page.

Husband Connolly, who joined her for part of the time, found paradise had its drawbacks, saying that the endless azure lagoons and perfect white beaches were all the f****** same. But Stephenson emerged renewed.

I’ve never felt so terrified and I’ve never felt so in touch with nature, she said while promoting her book of the voyage, Treasure Islands. I have a sense of being much stronger.

Now the couple are considering leaving LA and living permanently in their Highland retreat.

They are not alone. Nearly as many oldies as students now take gap years. And more and more of them are taking to the high seas.

Here are the stories of just a few of them.

Early on Friday morning Bill and Mindy Franklin let slip the mooring lines and eased their yacht out of Lagos marina in southern Portugal.

Under sunny skies they set course into the Atlantic, heading for Madeira and beyond that the Canaries, the Caribbean, the Pacific wherever they desired in their new life afloat. We are cruising along with dolphins playing at the bow, they reported later in a text message.

Like a growing number of a certain age, they have decided the best way to find adventure and escape modern stresses is to sail into the blue yonder.

It is a dream shared by many. And in an age of global communications and buoyant house prices, more people are turning the dream into a reality.

Speaking just before their departure, Bill, 54, said he had wanted to take yachting a bit further after years of tootling up and down the Solent. Then a happy confluence of events set him thinking.

His children were growing up, the engineering business he ran was winding down and house prices were riding high. If he didn’t do it now, he never would.

We had a big old draughty farmhouse we didn’t need so I thought, I’ll order the boat with the idea of winding up the business in a couple of years and going off. And that is exactly what we did.

He bought a 43ft Hallberg Rassy yacht and sold up in Bedfordshire. We are completely assetless apart from the boat, he said. The money’s in the bank, we have no cars, no house. It’s liberating. They can put down roots or anchors wherever they choose.

What does Mindy think about such upheaval? You’ve got to pick the right partner, he said. Mindy hides her light under a bushel in terms of her capabilities and willingness to do all this.

Their younger daughter Emma, 23, is joining them for the first six weeks of their voyage. They hope she and her elder sister, Lucy, 25, will fly out to meet them at other times on the odyssey, which is expected to last several years. The worst part is leaving elderly relatives behind.

We’ve dumped all the material things. It’s the human ties that are the hardest, said Bill. My mother hurt herself just as we were leaving. Mindy’s parents are both alive and rapidly approaching their eighties.

DESPITE such emotional tugs, the phenomenon of middle-age escape is spreading. A Mintel study published last month estimated that each year 200,000 older adults in the UKwere taking career breaks or pursuing early retirement.

Almost as many early retirees as students now take off on gap-year expeditions. Most go overland and spend about 5,000 a head. Sailing into the sunset is rarer and costs more but is still within the reach of anyone prepared to cash in their home.

It’s definitely getting more popular, it’s growing and growing, said Fred Barter, editor of the Cruising Association’s magazine. At the Southampton boat show this month I launched a book called “Seize the Day” on just that subject.He says he sold hundreds of copies.

Luxury boat sales are booming and exports are rising; turnover in the UK leisure marine industry has risen by more than 50% in five years.

Others join the booming business of professional adventure by paying specialist companies to take them as crew on ocean races. Last month saw the start of the 2005-6 Round the World Yacht Race, run by Clipper Ventures, which left from Liverpool. Participants splashed out about 25,000 for the 10-month voyage; another race is scheduled for 2007.

Most adventurers, however, get by on more modest means. Seize the Day, for example, is the second instalment of the epic story of Shirley and Peter Billing, an English couple who decided after a nasty car crash to change their lives and sail the world. They planned on a three-year trip; more than 20 years later they are still going, although they have periodically returned home.

They’ve been through Europe, the Atlantic, Pacific, Australia and this book takes them back to Cyprus, said Barter. You can live more cheaply on a boat than you can ashore. He reckons a couple could enjoy life afloat for about 7,000 a year.

It is not funds but the unpredictable, in the shape of storms or piracy, that tends to capsize plans. When the Billings anchored off Eritrea on the east coast of Africa, an army detachment boarded the boat and threw them in jail for a month on suspicion of being spies.

More recently, Michael Briant, a television director and sailor, was attacked by pirates when passing the coast of Yemen. They fired AK-47s, forced him to stop and boarded the yacht.

One of the pirates, said Briant, stuck his gun in my stomach and with his other hand made the universal gesture for money. Money, money, dollar, dollar, he screamed at me. Sure I said as calmly as I could.

Briant and his wife escaped with their lives and yacht but minus their dollars, radios and other valuables. Fortunately, however, such terrifying ordeals are rare.

Piracy is not really an issue, said Paul Miller of Underwriting Risk Services (URS), a Lloyds group that specialises in yachts. You get it in Asia, particularly the Straits of Malacca, but we don’t hear of many cases.

In Miller’s experience more mundane matters determine the success or failure of a trip. The key issues URS examines before insuring a yacht are the sailors skills and the number of crew.

It will cover couples sailing alone if they are experienced; if not, they want more crew on board, otherwise the physical effort of long-distance sailing can lead to exhaustion and disaster in heavy weather. It’s a big jump from sailing across the Channel to sailing across the Atlantic, said Miller.

But finding like-minded souls to share life on the ocean wave is not always easy. Even husbands and wives can be driven to mutiny.

WHEN Gwyneth Lewis, a poet from Cardiff, went to see a tarot card reader she was advised to buy a boat and watch out for her husband’s back pain.

What a load of rubbish, Leighton, her husband, said. I haven’t even got back pain. Within days he did and within a week he had seen a boat he wanted to buy.

Not long afterwards we were talking about renting out the house and sailing round the world, says Gwyneth, whose book on the subject, Two In A Boat: a Marital Voyage, was published this year.

Leighton is a former merchant seaman, but Gwyneth was a novice. She soon found that their relationship changed at sea, with Leighton displaying Captain Bligh traits when the going got tough.

Both marriage and boat need constant attention if they are to remain seaworthy, she noted.

They survived the storms; but Mark Bridgwood, a builder from Devon, had less luck. He and Tracey, his wife, sailed round the Mediterranean and used their ketch, Rebel, as a family home.

When their relationship ran on to the rocks, Bridgwood decided to sail to the Caribbean but turned back when he neared Portugal. His wife then secretly advertised the yacht for sale at a bargain price.

Incensed, Bridgwood last week rowed out to the yacht on the River Dart, smashed a seacock and watched it sink. His estranged wife and co-owner could hardly believe it. I’ve got nothing to lose any more, she said. All I’ve got is at the bottom of the river.

But if you can survive sailing round the world together in a cramped yacht, there must be something right with your relationship. When William Stares, 32, and Fiona Izat, 33, sailed out of Swansea marina in 2002, they didn’t know where it would lead. I hadn’t sailed before, but I wasn’t going to be left behind, said Izat. It can make or break you. There’s no way you can walk out, slam the door and drive away. It made them. Halfway round the world they married in Sydney, and in August, after 35,000 miles at sea, they arrived home. It’s been a big challenge, said Stares, but so incredibly rewarding. Fiona made all these sacrifices and life-changing decisions to do what I wanted to do. I was amazed I hadn’t asked her (to marry me) earlier.

Treasure Islands: Sailing The South Seas in the wake of Fanny and Robert Louise Stevenson – buy it on Amazon (UK only) and save 40%

Treasure Islands: Sailing The South Seas in the wake of Fanny and Robert Louise Stevenson – buy it on Amazon (UK only) and save 40% Chapman Piloting & Seamanship 64th Edition : The Boating World’s Most Respected Reference, Completely Updated & Revised with New Charts, Photographs & … Seamanship and Small Boat Handling – buy it from Amazon US

Chapman Piloting & Seamanship 64th Edition : The Boating World’s Most Respected Reference, Completely Updated & Revised with New Charts, Photographs & … Seamanship and Small Boat Handling – buy it from Amazon US