Assets of the Loss & Damage fund are currently standing at zero, but countries will be under pressure to contribute quickly. The speed at which this should be paid is open to debate and clearly depends on what each country can afford, but the total EU bill is relatively easy to calculate.

About $2 trillion of the $11.4 trillion is directly attributable to the EU itself, rather than being owed by its 27 member countries, because the basic tenets that the European Commission has promoted since it was first founded in 1952, encouraged, indeed coerced, its member states to burn fossil fuels.

Loss and damage refers to the most severe impacts of extreme weather on the physical and social infrastructure of poor countries, and the financial assistance needed to rescue and rebuild them.

It was the most contentious issue at the COP27 conference, and has been a long-running demand by developing countries since 1992. For nearly two weeks, the EU and the US refused demands from poor countries for a new fund to address loss and damage, arguing that existing funds should be redirected for the purpose. Early on Friday morning, the EU made a U-turn, to agree to a fund on condition that big economies and big emitters still classed as developing countries under the UNFCCC rules, which date back to 1992, should be included as potential donors, and excluded as recipients.

From its very first moment, the EU was all about burning energy – it had been brought into being to foster the burning of coal, the production of power, and the regulation of giant corporate interests.

It launched in 1952, called the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). In 2002 Romano Prodi said: “The ECSC was a courageous and hugely significant leap forward for Europe. It was Europe’s first step in pooling a part of each country’s sovereignty for the greater good of all who took part. It was the ECSC which first established shared, supranational institutions for Europe – the basis of the EU as we know it today and a milestone in political history. History will record the founding of the ECSC as a defining moment.”

The stated aim of the ECSC was “economic expansion, employment and better living standards.” They achieved all three – but at what cost?

The Coal and Steel Group had a High Authority to:

• supervise the market;

• monitor compliance with competition rules; and

• ensure price transparency

The aim of the 1952 treaty, as stated in its Article 2, was to contribute, through the common market for coal and steel, to economic expansion, employment and better living standards. Thus, the institutions had to ensure an orderly supply of coal and steel to the common market by ensuring equal access to the sources of production, the establishment of the lowest prices and improved working conditions. All of this had to be accompanied by the growth in international trade and the modernisation of production.

In creating a common market, the treaty introduced the free movement of products without customs duties or taxes. It prohibited discriminatory measures or practices, subsidies, state aids or special charges imposed by states and restrictive practices.

The Commissioners always took the EU roots in energy production to the furthest corner of the empire. Every state which joined the Union (1972 Denmark, Ireland, UK; 1985 Spain and Portugal etc etc) was sold an energy grid. Villages in Southern Europe which had done perfectly well until 1985, suddenly found their power supply massively enhanced. The same thing happened in Eastern Europe a decade later.

So from the very start, the EU was about enabling the economies (and in particular the largest manufacturers and corporations), to maintain the maximum rate of growth.

By the early 1960s there were already a clamour of warning about the effect of this policy on the environment. Environmental protests erupted across the continent. But they were ignored.

CO2 is primarily released through human activities like fossil fuel combustion, and today’s atmospheric concentrations exceed pre-industrial levels by 47 percent. At a cost of $400–$500 million per unit, commercial technology can capture carbon at roughly $58.30 per metric ton of CO2, according to a DOE analysis in 2021. This price is the basis for the calculation that follows.

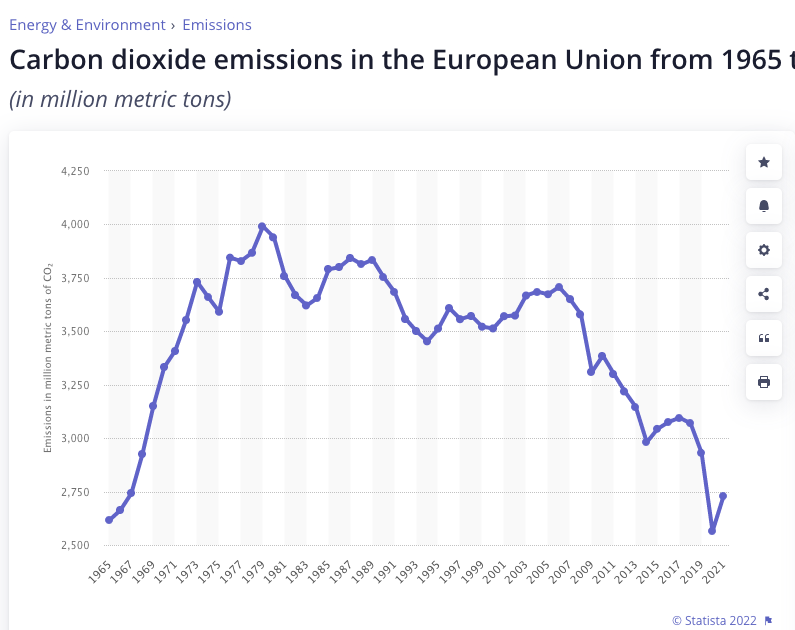

In 1979 alone, the peak year for all EU carbon emissions the total carbon emitted was 3,991 million tons of CO2. Assuming the cost of sequestering is the fair price to pay that means a total bill of $232.68 billion just for the year 1979. The average over the past 65 years since 1957 is more like 3 billion tons per year, which would equate to just $175 billion per year – multiply that up by 65 and the grand total CURRENTLY owed (it is still increasing) is $11.36 TRILLION dollars.

The precise amount that should be taken as the EU share of that total is open to debate. But it is clear that at least some of the impetus for the policies on carbon emissions came from the Berlaymont building in Brussels rather than from member states, or from the European Parliament. It is also the case that the EU commissioners could have been much more heavy-handed in the fines handed out to Europe’s largest polluters.

The estimate of $2 trillion owed by the EU directly could easily be raised in fines on Europe’s largest polluters.