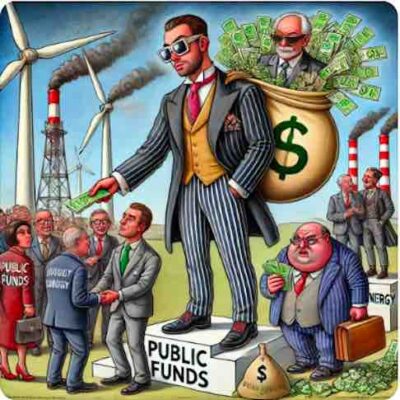

Sign up for Community Micropower in your Area

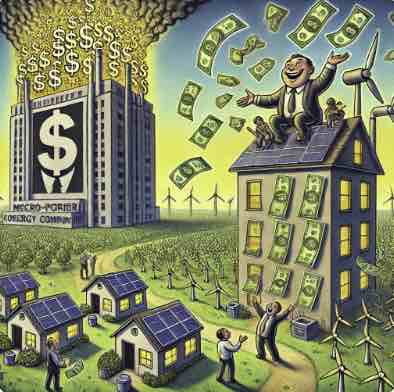

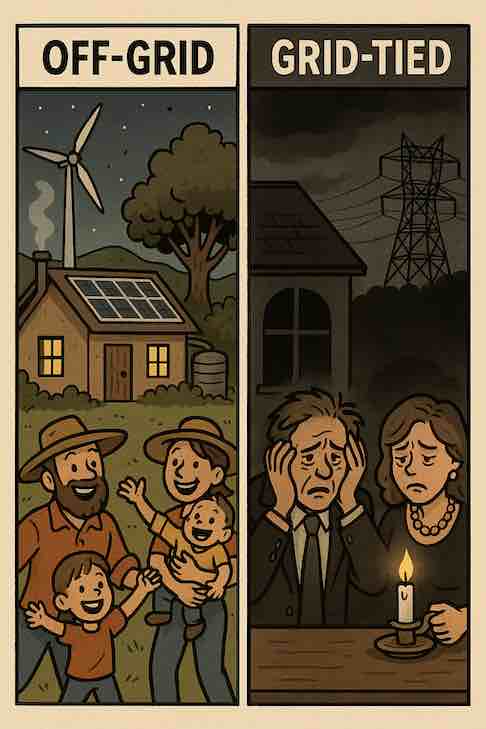

Find out how you can protect yourself from energy price rises, take control of your energy supply and reduce your environmental impact.

Meet people, share skills and resources, find land, more…

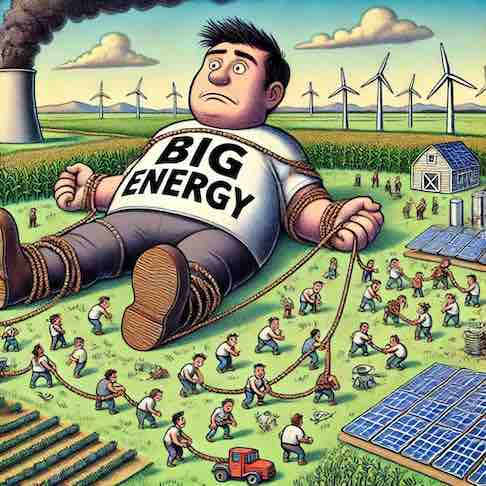

It’s hard going off grid for the first time, don’t try this on your. You can meet people who are looking to share land and pool resources. Add yourself to the map. Place yourself wherever you want in the world. It could be the place you live now or the place you want to go to.

It’s the quickest way to connect with like-minded people in your area.

JOIN US

Meet people, share skills and resources, find land, more…

It’s hard going off grid for the first time, especially on your own. You can meet people who are looking to share land and pool resources. Add yourself to the map. Place yourself wherever you want in the world. It could be the place you live now or the place you want to go to.

It’s the quickest way to connect with like-minded people in your area.

SIGN-UP TO OUR NEWSLETTER

UPLOAD

YOUR

FILMS

Can you help spread the word about off grid success stories? With a phone camera you can upload to our youtube channel!

If you currently live off grid anywhere in the world, please send us images and videos and tell us about yourselves.

Click below to upload your film and we’ll edit and share it with our online community.